POI Risk Calculator: How Opioids Impact Bowel Recovery

This tool helps you estimate your risk of postoperative ileus based on your surgery type and opioid use. Postoperative ileus (POI) is a common condition where bowel function slows or stops after surgery, often worsened by opioids. Learn how to reduce your risk.

Risk Assessment

Your Results

Estimated POI Duration: --

Estimated POI Risk: --

Recommendations

After surgery, many patients expect to feel better - but instead, they’re stuck with bloating, nausea, and no bowel movement for days. This isn’t just discomfort. It’s postoperative ileus - a common, costly, and often preventable condition worsened by opioids. While surgery itself disrupts gut function, it’s the pain meds we rely on that often push the body over the edge. The result? Longer hospital stays, higher costs, and unnecessary suffering.

What Exactly Is Postoperative Ileus?

Postoperative ileus (POI) isn’t a blockage. It’s when your intestines temporarily stop moving normally after surgery. You might feel full, bloated, nauseous, and unable to eat or pass gas. Your stomach feels tight. Your bowels are silent. This isn’t normal recovery - it’s a physiological shutdown.

POI typically lasts 2 to 5 days, but when opioids are involved, it can stretch to 7 days or more. The American Society of Anesthesiologists defines clinically significant POI as lasting longer than 3 days. That’s not just inconvenient - it’s dangerous. Delayed bowel function increases the risk of infection, pneumonia, and even readmission. In the U.S., POI adds an average of 2 to 3 days to hospital stays and costs the system about $1.6 billion each year.

Why Opioids Make It Worse

Opioids are great at blocking pain - but they’re terrible for your gut. They bind to mu-opioid receptors in the walls of your intestines, slowing or stopping the muscle contractions that move food along. This isn’t just a side effect - it’s a direct, dose-dependent hit to your digestive system.

Studies show that patients receiving 5 to 10 mg of morphine equivalents per hour after surgery experience up to a 200% delay in gastric emptying. Colonic motility drops by as much as 70%. You’re not just constipated - your entire digestive system is on pause.

The symptoms are unmistakable: hard, dry stools (46-81% of patients), straining (59-77%), bloating (40-61%), and abdominal distension (28-58%). Many patients report feeling like their stomach is a balloon. One survey of 1,247 surgical patients found those who got more than 50 morphine milligram equivalents in the first 48 hours had 3.2 times more severe bloating and took nearly 3 full days longer to have their first bowel movement.

How POI Develops: Three Mechanisms at Work

POI isn’t caused by one thing. It’s a mix of three overlapping problems:

- Neurogenic - Surgery triggers a stress response that shifts your nervous system into fight-or-flight mode. This shuts down digestion. The parasympathetic system, which normally keeps things moving, gets suppressed.

- Inflammatory - Cutting into tissue releases cytokines and other inflammatory signals. These chemicals directly interfere with gut nerve function and muscle activity.

- Pharmacologic - Opioids lock onto receptors in your gut, blocking signals that tell muscles to contract. Even endogenous opioids released during surgery make things worse.

These factors work together. A patient having abdominal surgery gets inflammation from the incision, nerve disruption from anesthesia, and then a high-dose opioid infusion. It’s a perfect storm.

Traditional Treatments Don’t Work Well

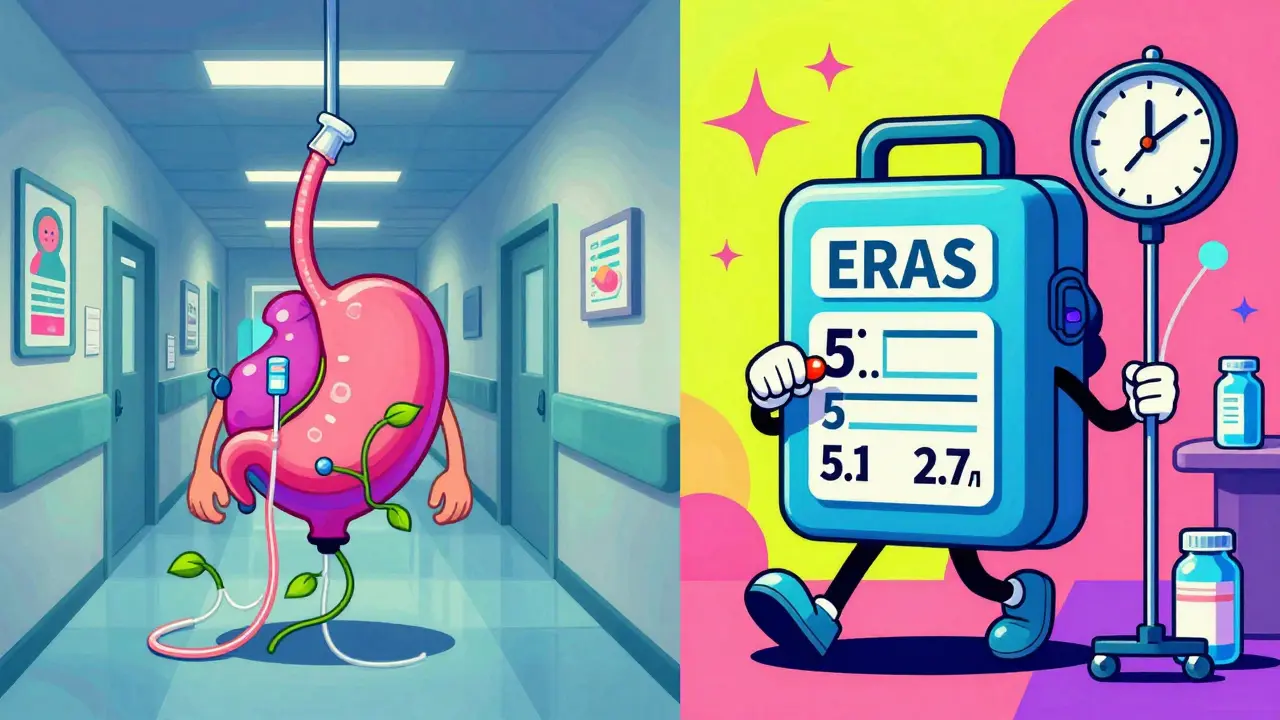

For years, the go-to fix was the nasogastric tube - a big tube shoved through the nose into the stomach to suck out fluid. But studies show it only reduces POI duration by 12% compared to doing nothing. It’s uncomfortable, increases infection risk, and doesn’t fix the root cause.

Other old-school methods - like lying still, waiting it out, or giving laxatives - are equally ineffective. Laxatives don’t help if the gut isn’t moving at all. Waiting only extends the problem.

What works better? It’s not about fixing the symptoms - it’s about preventing the problem from happening in the first place.

Prevention: The Real Solution

The best treatment for POI is not giving it a chance to start. That’s where multimodal analgesia comes in - using a mix of non-opioid painkillers to reduce or eliminate opioid use.

Here’s what works:

- Acetaminophen (IV or oral) - Given every 6 hours, it cuts opioid needs by 30-40%.

- Ketorolac (IV NSAID) - Reduces inflammation and pain. Avoid in patients with kidney issues or bleeding risk.

- Regional anesthesia - Spinal or epidural blocks dramatically lower opioid requirements. One study showed orthopedic patients on epidurals had POI lasting 3.8 days instead of 5.2.

- Limiting opioids - The ERAS Society recommends keeping total opioid use under 30 morphine milligram equivalents in the first 24 hours. That cuts POI risk from 30% to 18%.

One hospital system reduced opioid use by 60% after switching to this approach. POI rates dropped by 35%. Patients went home sooner. Costs fell.

Specialized Medications That Actually Help

When opioids are necessary, there are drugs designed to block their gut effects without touching pain control.

Alvimopan and methylnaltrexone are peripheral opioid receptor antagonists. They sit in the gut and block opioids from slowing things down - but don’t cross the blood-brain barrier, so they don’t interfere with pain relief.

Studies show:

- Alvimopan shortens time to bowel recovery by 18-24 hours after abdominal surgery.

- Methylnaltrexone speeds up bowel function by 30-40% in opioid-tolerant patients.

But they’re not for everyone. They’re contraindicated if there’s a real bowel obstruction (which happens in 0.3-0.5% of cases). And they’re expensive - methylnaltrexone costs $147.50 per dose. That’s why experts recommend using them only in high-risk patients: those having abdominal surgery, opioid-naive individuals, or those getting more than 40 morphine milligram equivalents in 24 hours.

Simple, Low-Tech Strategies That Work

You don’t always need drugs. Some of the most effective tools are free and simple:

- Early ambulation - Getting out of bed within 4 hours after surgery reduces POI duration by 22 hours. Walking stimulates gut nerves and resets motility.

- Chewing gum - It tricks your brain into thinking you’re eating. Studies show chewing gum 4 times a day reduces time to first flatus by 10-14 hours. It’s not a cure, but it’s a cheap, safe boost.

- Early oral intake - Letting patients sip water or eat light snacks within 6-12 hours after surgery (if they’re not nauseous) keeps the gut active.

One nursing unit implemented a “POI bundle”: gum chewing, walking within 6 hours, and scheduled IV acetaminophen. They cut average POI duration from 4.1 days to 2.7 days across 347 patients.

What Hospitals Are Doing Right (and Wrong)

Not all hospitals treat POI the same way. There’s a big gap between top performers and everyone else.

Academic medical centers - where protocols are standardized - have 92% adoption of formal POI prevention programs. They track outcomes: time to first flatus, time to bowel movement, and ability to tolerate 1,000 mL of fluids. If a patient hasn’t passed gas by 72 hours or hasn’t eaten by 24 hours, the team intervenes.

Community hospitals? Only 64% use any structured approach. Rural facilities? Just 28%. The result? POI lasts 3.2 days on average in academic centers - but 5.1 days in rural ones. That’s nearly two extra days of hospitalization, pain, and cost.

Barriers? Resistance from anesthesia teams used to opioids. Nurses not trained on early mobilization. Poor documentation of opioid doses. One study found only 42% of nurses followed early ambulation protocols in the first months of implementation.

The Economic Impact Is Real

POI isn’t just a medical problem - it’s a financial one.

The global market for POI management is projected to hit $2.1 billion by 2029. Why? Because hospitals are being penalized. Under Medicare’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, facilities with high POI-related readmissions lose money - up to $187,000 per facility in 2022.

But prevention pays off. One hospital system saved $2,300 per patient by reducing POI duration by 1.8 days. That’s $2.3 million saved annually for a mid-sized hospital. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality estimates that if 90% of U.S. hospitals adopted full POI protocols, the country could save $7.2 billion a year.

What’s Next? Emerging Solutions

Research is moving fast:

- Extended-release alvimopan is in Phase III trials - could be available by 2026.

- AI prediction models at Mayo Clinic use 27 pre-op factors to identify high-risk patients with 86% accuracy.

- Fecal microbiome transplants are being tested for stubborn cases - early results show 40% improvement in motility.

- Naltrexone implants for long-term gut blockade are in preclinical testing.

These aren’t sci-fi. They’re the next step in making POI a relic of the past.

Bottom Line: You Can Avoid This

If you’re facing surgery, ask your team: “What are you doing to prevent postoperative ileus?”

Don’t assume opioids are the only option. Push for a plan that includes:

- Minimizing opioid use

- Starting non-opioid pain control before surgery

- Getting up and walking as soon as possible

- Chewing gum after surgery

- Knowing when to ask for a peripheral opioid blocker if opioids are needed

Postoperative ileus isn’t inevitable. It’s predictable. And with the right approach, it’s preventable. The tools are here. The evidence is clear. The only question is: will your care team use them?

How long does postoperative ileus usually last?

Typically, postoperative ileus lasts 2 to 5 days. If it lasts longer than 3 days, it’s considered clinically significant and may require intervention. Opioid use can extend this to 7 days or more, especially in abdominal surgeries or patients receiving high doses.

Can I avoid opioids completely after surgery?

Many patients can avoid opioids entirely with multimodal analgesia - using acetaminophen, NSAIDs like ketorolac, and regional anesthesia (such as spinal or epidural blocks). Studies show this approach reduces opioid use by 30-60% and cuts POI risk by 25-35%. However, for major surgeries or severe pain, some opioids may still be needed - but kept to the lowest effective dose.

Is chewing gum really helpful after surgery?

Yes. Chewing gum mimics eating, which triggers vagus nerve signals to stimulate gut motility. Studies show it reduces time to first flatus by 10-14 hours and time to first bowel movement by about 1 day. It’s low-cost, safe, and recommended by ERAS guidelines for most patients after abdominal surgery.

What are the risks of using methylnaltrexone or alvimopan?

These drugs are generally safe but are contraindicated if there’s a mechanical bowel obstruction - which occurs in 0.3-0.5% of surgical patients. They’re also expensive (around $147-$150 per dose), so they’re typically reserved for high-risk patients: those having abdominal surgery, opioid-naive individuals, or those receiving more than 40 morphine milligram equivalents in 24 hours.

Why do some hospitals still rely on nasogastric tubes for POI?

Some hospitals still use nasogastric tubes out of habit or lack of updated protocols. But research shows they provide only a 12% reduction in POI duration compared to standard care - and they’re uncomfortable and increase infection risk. Modern guidelines recommend avoiding them unless there’s a true ileus with vomiting or distension unresponsive to other measures.

Can opioid withdrawal cause symptoms that mimic POI?

Yes. If opioids are reduced too quickly after surgery - especially in patients who received high doses - withdrawal symptoms like nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal cramping can occur. These can be mistaken for POI. The key is tapering opioids gradually and using non-opioid alternatives to bridge the gap.

Paul Huppert

December 30, 2025 AT 20:41Man, I had this after my appendix surgery. Thought I was dying. Turns out it was just the morphine doing its thing. Glad to see they’re finally pushing non-opioid stuff.

Emma Hooper

December 30, 2025 AT 23:38Chewing gum? Really? That’s the best we’ve got? I mean, I get it - it’s cheap and harmless - but it feels like we’re treating a heart attack with aspirin and a pep talk. Someone’s gotta fix the system, not just hand out gum like it’s candy at a parade.

Deepika D

January 1, 2026 AT 15:50As a nurse who’s seen this play out a hundred times, I can tell you - the real game-changer is early mobility. I used to think meds were the answer, but nope. Get ‘em out of bed within 4 hours, even if they’re wobbly. Walk them to the bathroom. Sit them in a chair. It’s not rocket science. And guess what? Patients feel better faster. They stop crying. They start joking. It’s not just about bowels - it’s about dignity. I’ve seen patients who refused to walk on day one, and by day three, they’re doing squats in the hallway. That’s the magic. No drug can replicate that. Just human presence, gentle pressure, and a little patience. Hospitals need to stop treating this like a pharmacy problem and start treating it like a human problem.

Stewart Smith

January 2, 2026 AT 21:10So we’re paying $150 per dose to unblock a gut… but we won’t pay for a physical therapist to walk a patient for 10 minutes? Yeah, that tracks.

Branden Temew

January 4, 2026 AT 09:46It’s funny how we’ll spend millions on a drug that blocks opioids in the gut but won’t spend $20 on a walking cane for a 70-year-old after surgery. We don’t treat the system - we treat the symptom. And then we call it innovation.

Frank SSS

January 5, 2026 AT 00:22Let me guess - the next thing they’ll tell us is that crying helps digestion too. This whole post feels like a pharma ad disguised as medical advice. Opioids are bad. Gum is good. Alvimopan costs $147.50. Who’s getting rich here?

Hanna Spittel

January 5, 2026 AT 21:48AI predicting POI? 😏 Meanwhile, my hospital still uses paper charts and nurses forget to give acetaminophen. This is all just tech glitter on a broken system. Also, I think the FDA is being paid off. 🤫💊

Brady K.

January 7, 2026 AT 02:43Let’s cut through the jargon: POI isn’t a medical condition - it’s a systemic failure of pain management culture. We’ve built a healthcare economy around opioid dependency, then act shocked when the gut shuts down. The real villain isn’t morphine - it’s the reimbursement model that rewards volume over outcomes. Until we pay for recovery, not just intervention, we’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic. Alvimopan? A Band-Aid on a hemorrhage.

anggit marga

January 8, 2026 AT 20:33Why are we even talking about this? In Nigeria we just give them pepper soup and tell them to walk. Works better than all these fancy drugs. You guys overthink everything