Imagine needing a life-saving drug but having to pay three months’ wages for a single month’s supply. This isn’t a scene from a dystopian novel-it’s the daily reality for millions in low-income countries. The solution isn’t magic. It’s not a new invention. It’s generics: the same active ingredients as brand-name drugs, sold for a fraction of the price. Yet, despite cutting drug costs by up to 80%, generics still don’t reach the people who need them most.

Why Generics Are the Only Real Hope

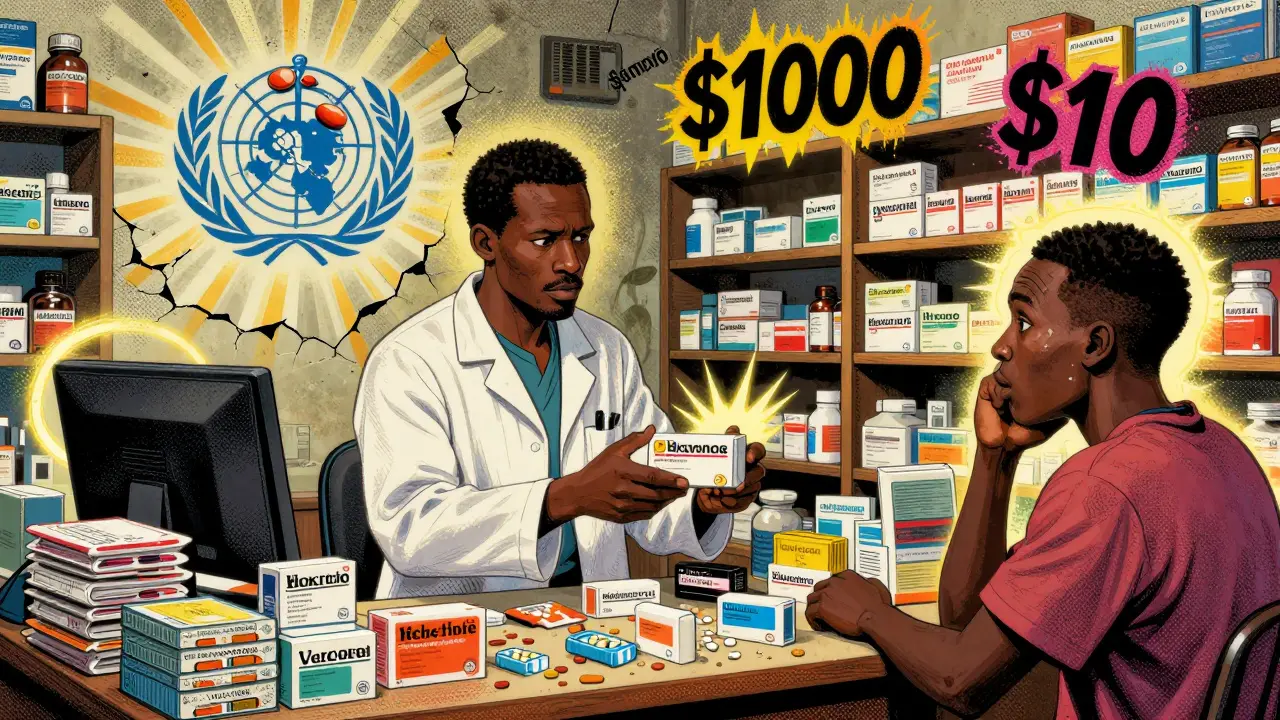

Generics aren’t cheap knockoffs. They’re identical in strength, dosage, and effectiveness to the original drugs. The difference? No patent. No marketing. No fancy packaging. That’s why a month’s supply of generic antiretroviral drugs for HIV, which once cost over $10,000, now costs less than $100 in many African countries. This drop didn’t happen by accident. It came from legal changes like the 1995 TRIPS Agreement, which let developing nations bypass patents during public health emergencies. Without that flexibility, millions wouldn’t be alive today.The World Health Organization lists 43 essential medicines that every country should have available. For HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria, generics have been the backbone of global treatment programs. In sub-Saharan Africa, where HIV rates are highest, generic antiretrovirals helped cut death rates by more than half in just 15 years. That’s the power of affordability. When a drug drops from $1,000 to $10, health systems can treat 100 times more people with the same budget.

The Stark Reality: 5% Market Share in LMICs

Here’s the problem: even though generics work, they’re barely used in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). In the U.S., unbranded generics make up 85% of all prescriptions. In LMICs? Only 5%. Why such a gap?It’s not that people don’t want them. It’s that they often don’t have access. Public clinics run out of stock. Private pharmacies stock only branded versions because they make more profit. Patients, desperate and distrustful after being sold fake drugs in the past, pay more for names they recognize-even if those drugs are just repackaged generics with a higher price tag.

Supply chains are broken. In rural areas, medicines might sit in warehouses for months because roads are bad, refrigeration is unreliable, or customs delays hold up shipments. One study found that in many African countries, essential medicines are out of stock more than 30% of the time. Even when generics are available, they’re not where people need them.

Who’s Making Generics-and Who’s Not Helping

Five big generic manufacturers-Cipla, Hikma, Sun Pharma, Teva, and Viatris-produce over 90% of the off-patent drugs needed in LMICs. They make them. They ship them. But here’s the catch: most don’t design their business models to reach the poorest patients.The Access to Medicine Foundation found that for the 102 priority medicines, these companies had clear access plans for only 41 of them. And even then, few included pricing strategies for people who pay out of pocket. If you’re a farmer in Malawi earning $2 a day, a $5 generic still costs half your daily income. That’s not affordable. That’s a luxury.

Meanwhile, big pharma companies like Novartis and Pfizer have programs that offer discounts or free drugs in poor countries. But they rarely say how many people actually get them. Transparency is missing. Without knowing who’s being helped and where, it’s impossible to fix the gaps.

Regulation, Taxes, and Trade Barriers-The Hidden Costs

It’s not just about making drugs cheap. It’s about keeping them cheap. Many low-income countries still charge import tariffs on medicines. Some tax them at 10-20%. In places like Nigeria and Kenya, these fees can add 30% to the final price of a generic drug. That’s like paying $13 for a $10 medicine.Regulatory systems are slow, too. A generic drug approved in the U.S. or EU might take years to get clearance in a low-income country because the local health agency lacks staff, funding, or technical training. Meanwhile, patients die waiting.

The Geneva Network recommends simple fixes: cut import taxes, remove trade barriers, and speed up approvals. These aren’t radical ideas. They’re basic public health economics. Yet few governments act on them.

Why Patients Still Choose Brand Names

There’s a deep distrust of generics in many communities. Why? Because fake drugs are everywhere. In some regions, up to 1 in 10 medicines sold are counterfeit. People have seen relatives die after taking fake antibiotics. So when a pharmacist offers a generic version, patients say no-even if it’s real.Branded drugs, even when overpriced, carry a false sense of safety. The same active ingredient, same results, but a different label. It’s psychology. And it’s expensive. A course of generic tuberculosis treatment might cost $20. The branded version? $200. But patients pay the $200 because they’re scared.

Education matters. Community health workers who explain that generics are the same-tested, approved, safe-can change behavior. In Uganda, pilot programs where nurses handed out fact sheets with photos of real vs. fake pills cut refusal rates by 60% in six months.

What’s Working: Real Examples

Not all hope is lost. Some models are proving that change is possible.In Rwanda, the government partnered with generic manufacturers to buy antiretrovirals in bulk, negotiated prices down to $18 per patient per year, and set up a national distribution system that reaches even remote clinics. Today, over 95% of HIV-positive people in Rwanda are on treatment.

In India, the public sector buys 80% of its medicines through centralized tenders, forcing manufacturers to compete on price. As a result, India supplies over 50% of the world’s generic drugs. That’s not luck. That’s policy.

Even in places with weak systems, innovation is happening. Gilead ran HIV prevention trials in Uganda using a long-acting injectable, delivered directly to villages. Merck and Novartis teamed up with African health groups to test new malaria drugs in low-income countries-finally including local populations in clinical research instead of just using them as test subjects.

The Bigger Picture: Poverty, Health, and Broken Systems

Every year, 100 million people are pushed into extreme poverty because they can’t afford healthcare. Nearly 90% of people in developing countries pay for medicine out of their own pockets. That means families sell livestock, pull kids out of school, or skip meals just to buy insulin or blood pressure pills.The Abuja Declaration in 2001 asked African nations to spend at least 15% of their budgets on health. In 2022, only 23 of 54 African countries met that target. Most spend less than 5%. Without public investment, you can’t have public health.

Generics can’t fix everything. But they can fix a lot-if the system lets them. No country has achieved universal health coverage without affordable medicines. No one.

What Needs to Change

There’s no single fix. But here’s what works when done together:- Remove taxes and tariffs on essential medicines-every country should make them zero-rated.

- Speed up approvals by letting countries rely on WHO or EU pre-qualification instead of starting from scratch.

- Train community health workers to educate patients on generic safety and effectiveness.

- Build stronger supply chains with solar-powered fridges, mobile tracking, and local distribution hubs.

- Require transparency from pharma companies: how many patients got the drug? Where? At what price?

- Invest in public health budgets-even 10% of GDP is better than 3%.

Generics are not the problem. They’re the answer. The problem is the system that keeps them out of reach.

Are generic drugs safe in low-income countries?

Yes-if they’re from approved manufacturers and properly regulated. Many generics used in low-income countries are made by companies like Cipla or Hikma, which supply WHO-prequalified medicines to UN agencies. These drugs go through the same testing as brand-name versions. The real danger comes from counterfeit drugs sold on the black market, not from legitimate generics. Training health workers and improving supply chain tracking can reduce fake drug risks.

Why don’t governments buy more generics?

Many do-but not enough. Budgets are tight, and corruption sometimes leads to contracts going to higher-priced brands. Some officials believe branded drugs are better, even when evidence says otherwise. Others lack the systems to manage bulk procurement. When governments use centralized purchasing and transparent bidding, they can get generics at prices as low as $0.05 per dose for malaria drugs.

Can low-income countries make their own generics?

Yes, and some already do. India and South Africa are major generic producers. Kenya, Nigeria, and Ethiopia are building local manufacturing capacity. But they need investment in labs, trained chemists, and regulatory bodies. The WHO and UNDP have helped set up regional production hubs in Africa to reduce reliance on imports. Local production cuts costs, creates jobs, and ensures supply during global shortages.

Do pharmaceutical companies help or hurt access to generics?

It’s mixed. Some generic makers focus on profit, not access. Some big pharma companies offer discounts or voluntary licenses, but rarely disclose how many patients benefit. Others still push for longer patent extensions or data exclusivity, which delays generics. Companies like Gilead and Merck have started including LMICs in clinical trials and offering tiered pricing, which is progress. But without mandatory transparency, it’s hard to know who’s truly helping.

What can ordinary people do to improve access?

Support organizations that fund medicine delivery in poor countries. Advocate for policies that remove tariffs on essential drugs. Raise awareness about the safety of generics. If you’re in a high-income country, pressure your government to fund global health programs like the Global Fund or PEPFAR. Real change happens when public pressure forces governments and companies to act.

The future of global health doesn’t depend on new breakthroughs. It depends on making what already works-affordable, effective generics-available to everyone. Not just in cities. Not just for the insured. For the farmer in Mali, the mother in Bangladesh, the child in Haiti. That’s not idealism. It’s basic justice.

Aboobakar Muhammedali

December 20, 2025 AT 11:08I remember seeing a man in Delhi crying because he couldn’t afford his dad’s blood pressure pills

He sold his bicycle just to buy one month’s supply

Generics saved my cousin’s life with TB-$3 for a full course

Why do we act like this is normal?

Alana Koerts

December 20, 2025 AT 17:27Generics are fine but you’re ignoring quality control issues in places like Nigeria and Pakistan

Most of the ‘generic’ supply chain is a scam

WHO prequalification doesn’t mean squat if local pharmacies are selling chalk powder labeled as antiretrovirals

Dikshita Mehta

December 22, 2025 AT 05:26Actually, the WHO prequalification system is rigorous-it’s the only global standard that tests for bioequivalence, stability, and purity

Counterfeit drugs are a problem, yes, but they’re mostly sold illegally on the black market, not through正规 channels

India’s Central Drugs Standard Control Organization has one of the strictest regulatory frameworks in the developing world

And countries like Rwanda and Ghana have built transparent procurement systems that cut out middlemen

The real issue isn’t the generics-it’s the lack of investment in logistics and training

Most clinics don’t even have refrigerated storage, so even safe drugs spoil before they reach patients

Fix the supply chain, not the medicine

pascal pantel

December 23, 2025 AT 18:05Let’s be real-the whole generics narrative is a neoliberal fantasy

You think a $10 ARV is affordable for someone making $2/day? That’s 5 days of food

And WHO’s ‘prequalified’ manufacturers? Most are subsidiaries of Big Pharma subsidiaries

Teva owns 3 of the top 5 generic suppliers

It’s not access-it’s profit redistribution with a different label

Real solution? Abolish patents entirely. Not ‘flexibilities’-total dismantling

Until then, you’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic

Gloria Parraz

December 24, 2025 AT 02:30What Dikshita said is exactly right

It’s not about the drugs-it’s about the system

But here’s the good news: change is happening

Rwanda didn’t just get lucky-they built a national logistics network with drones and solar fridges

India’s public procurement system is now a global model

And community health workers in Uganda? They’re literally saving lives by showing people real pills vs fake ones

It’s not glamorous, but it works

We just need to fund it, scale it, and stop pretending this is too hard

Kathryn Featherstone

December 25, 2025 AT 09:18One thing no one talks about: cultural stigma

In rural areas, people believe branded drugs are ‘stronger’

They think if it doesn’t come in a fancy bottle with a logo, it’s not real medicine

That’s why education matters more than price

One nurse in Malawi told me she carries a small card with photos of real vs fake pills

She shows it to every patient

Refusals dropped by 70% in six months

Simple. Human. Effective

Nicole Rutherford

December 26, 2025 AT 22:34Wow. So you’re saying the solution is to just trust the same corrupt governments that steal healthcare funds?

Generics won’t fix corruption

Generics won’t fix broken roads

Generics won’t fix people who’d rather sell medicine for profit than save lives

You’re romanticizing a system that’s been failing for decades

Stop pretending this is about health. It’s about guilt

Chris Clark

December 26, 2025 AT 23:38Yo I was in Nairobi last year and saw a guy buy a branded antibiotic for $15

Turns out it was the exact same pill as the $1 generic next to it

Same packaging, same batch number, just a sticker over the label

Pharmacies do this all the time

People think they’re getting something better

They’re not

They’re just getting scammed harder

And yeah, some of those ‘generic’ batches? They’re fake

But most? They’re legit

Just need better labeling and more community trust

Also-why do we still call them ‘generics’? Sounds like a discount brand

Maybe we should just call them ‘medicines’

William Storrs

December 27, 2025 AT 21:25Look-I’ve worked in 12 low-income countries

Generics are the only reason millions are still alive

Yes, the system is broken

Yes, corruption exists

Yes, people are scared

But here’s what I’ve seen: when you give people real information, real access, and real dignity-they choose the right thing

It’s not magic

It’s just basic human decency

And we’re not doing enough to make that happen

So let’s stop talking about why it can’t work

And start building the systems that make it possible